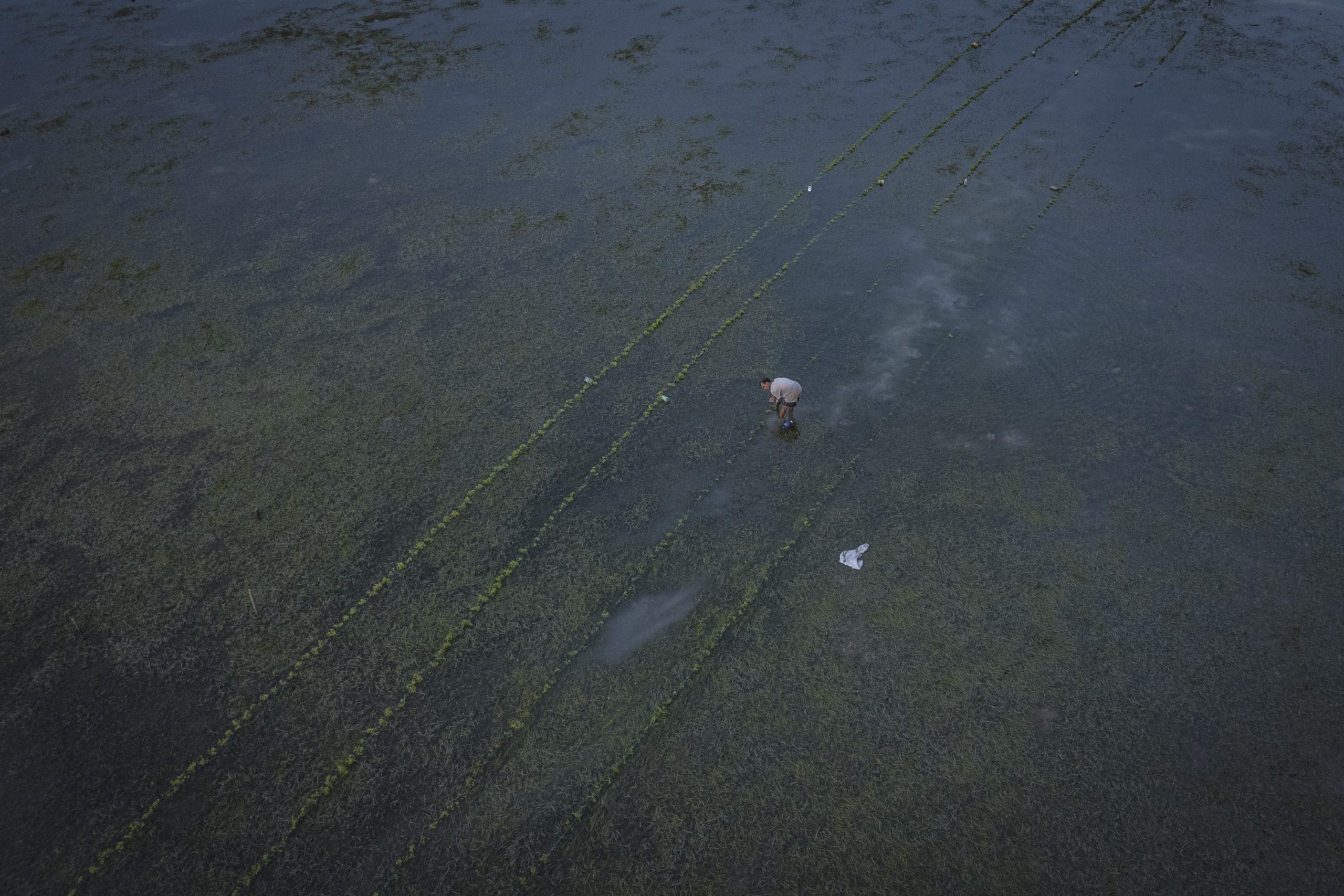

The sea in Bondo Boghila, Kahona Village, stretches wide. On an afternoon in mid-May 2025, when the sea was receding, some seaweed farmers were seen walking along the shore, picking up the leftover seeds fallen from the cultivation ropes.

In one of the houses, Kristina Dairo Loba enthusiastically lifted the seaweed rope tied with seeds. “This can be a main job now. The children can go to school,” she said.

In this coastal area, 10 fishermen’s groups are covered in the Inclusive Rural Community Livelihood Development Program in Eastern Indonesia (BangKIT) by BaKTI Foundation.

BaKTI Foundation is a non-profit organization that provides facilitation for poor communities. Fisherman’s groups are one of its development targets. This seaweed cultivation group planted seeds disregarding the eligibility standards. As a result, the seaweed stunted.

Kristina said they planted recklessly before participating in the BangKIT Program. There was no proper seed selection. The space between seeds is only around 2 centimeters. “After the training by BangKIT, we realized that planting distance matters too. The seeds should also be good,” she said. “We used to plant random seeds, both old and young.”

In this area, seaweed is planted along the coastline accessible by the tide. Approaching the evening, the sea recedes, and fishermen will harvest or plant seaweed. The seaweed does not float. The rope is stretched and tied with poles at each end, then stuck into the ground.

One stretch is 50 meters long. And harvested after two to three weeks. Using the previous planting system, one stretch would only produce one to one and a half sacks. “Now we can have up to three sacks,” said Kristina.

The seaweed was dried for only one day. It was very cheap. In the BangKIT Program, in collaboration with the Fisheries Office of Southwest Sumba, drying is done for a minimum of two days. If it is cloudy, it will take up to three days for the seaweed to dry. “Now look, the seaweed is big. It used to be small and thin. That’s why it was very cheap, less than 5 thousand rupiahs,” said Kristina.

After selecting good seeds, the seaweed is healthier. The price is a lot better, too. “Indeed, two years ago, the price of seaweed was up to 32 thousand rupiahs. Now it is 13 thousand rupiahs. Much better now,” she continued.

Creating Changes

Kristina stretched 10 ropes of seaweed. All harvested at the same time. Kristina and her husband will be very busy on the coast when the harvest season arrives. “Seaweed requires very little maintenance. It’s planted, then harvested,” she said.

Kristina has five children. One of them is working, one is in college, and the others are in junior high school, elementary school, and kindergarten. Her husband works in the field, but spends more time managing the seaweed.

Bondo Boghila is close to the sea, making the land dry and barren. The gardens are idle. The majority of farmers have switched to planting seaweed.

Kristina is part of the Batu Karang Group, which has 10 members. This group received in-kind assistance, namely ropes, ropes to tie up seeds, and seeds. “They accompany us. See our work. That’s why we know that planting seaweed requires specific techniques,” she said.

Now, in one harvest, Kristina can get 10 to 20 sacks of raw seaweed. It becomes 2 sacks in a dry state. One sack weighs 90 kilograms. “The seeds and the planting distance are good now. We can harvest per week,” she said.

Fisherman’s family, with a harvest similar to Kristina’s, can earn 1 million rupiahs per month. “With this, the children can go to college and school. It was impossible before,” she said.

Yohanis Kondi, another seaweed farmer who is not part of a group, is also very happy. “I haven’t joined a group yet. I saw my friends apply planting distance, I did the same, and the results were good,” he said.

Seaweed cultivation has been known by the coastal community of Bondo Boghila for several years. However, due to poor planting patterns, many of the seeds died. “Now, none of the seeds die,” he said.

Yohanis smiled happily. He said that now, seaweed farmers are not only talking about failures and difficulties. They are enthusiastically sharing stories of changes.

Ita Kondi, Kristina’s daughter, who is in junior high school, was also excited. She always accompanies her mother in her rest house on the coast. Their house is on the main road of the village, which is about four kilometers from the coast.

Ita is usually in charge of bringing food to the coast for her mother. Around eight in the evening, she returns home. “I like to stay here too when the seaweed is plentiful (harvested),” she said. “I like it. Helping my mother, untying the seaweed. Or helping to lift it after drying it,” she continued.

Ita’s younger sibling, who is at the primary school, enjoys playing in the beach sand. Kristina does not stop her. She is happy. “Children see how their parents work. And, playing on the beach is less dangerous, they’re just running around,” she said.

In mid-May 2025, approaching six in the evening, the sun was setting. She lifted a roll of the stretch ropes. She walked carefully down the dune on the coast, her body looked like a silhouette.

Her child, who is at the primary school, followed her from behind, running. A few meters later, the child stopped. Kristina continued walking until her calves were submerged by seawater. From a distance, she planted the stretch poles.

Rechecking the stretch ropes. Then, walked back. Her clothes and pants were wet. She stepped onto the bamboo floor of the terrace. Night had come. It was time for Kristina to rest, and the next afternoon, she would return to the sea to check the ropes, making sure none of her seeds had come loose because of the waves. “If some are missing, they will be added later,” she said.